Get the help you need right now 855-900-8437 Get Help Now

Get the help you need right now 855-900-8437 Get Help Now

Yarmouth, MA Local 2122 member Chuck Talbott t, a 27-year veteran of the fire service, has seen it all. Because of the traumatic events he witnessed, Talbott struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder throughout his career. When his symptoms devolved into alcoholism and forced him into retirement, enough was enough.

Talbott (left) with his mentor, who struggled with PTSD and substance abuse after a two-alarm fire early in his career.

From his youngest years, Talbott knew he wanted to be a fire fighter.

“My grandfather worked for the fire department,” he says. “It always fascinated me. I knew that’s what I wanted to do.”

So when he turned 18, he joined too.

“Like most people, what I loved most was the excitement of the job and being able to help people who can’t help themselves. My station ran about 7,000 calls a year, so we were very busy, and you never knew what was going to happen. I was a paramedic as well, so we did both jobs,” he says.

But 27 years later, Talbott found himself in front of his fire department and Local 2122 union leaders facing a decision: disciplinary action or retirement.

His drinking, fueled by post-traumatic stress disorder, was out of control. Talbott chose to retire.

Post-traumatic stress disorder affects fire fighters at about twice the rate of the general population. We know that now. But when Talbott was in the fire service, the awareness wasn’t there.

“The most challenging part of the job isn’t physical,” he explains. “It’s seeing things the human mind wasn’t designed to see. There are people that you won’t be able to help, or situations you won’t be able to mitigate. That is the most frustrating and mentally challenging thing about being a fire fighter.”

Unlike some fire fighters who cite specific incidents that led to their post-traumatic stress or behavioral health issues, Talbott says his diagnosis was a cumulative result of all the bad calls he’d seen throughout his almost three decades in the fire service.

Once the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder set in, Talbott’s life started to fall apart.

“I became angrier and more withdrawn at work,” he says. “I stayed in my office, away from people. It cost me my relationship. I became isolated because, in the fire service, showing signs of weakness used to be like sharks in bloody water.”

“The most challenging part of the job isn’t physical – it’s seeing things the human mind wasn’t designed to see. There are people that you won’t be able to help, or situations you won’t be able to mitigate.”

– Chuck Talbott

Alcohol was a normal part of everyday life for Talbott’s (center) family.

“The more I immersed myself in work, the more my personal life suffered. The thing that made it more tolerable was drinking.”

When Talbott was a fire fighter, he and his colleagues embraced a “work hard, play hard” mentality. Back then, he says it was common to go to the bar with the guys after your shift to throw a few back and burn off steam.

Talbott found solace from post-traumatic stress in alcohol. Without accountability at home — he never married or had children — he felt empty.

“Work was the bright spot of my existence,” he says. “The rest of my life wasn’t fulfilling. The more I immersed myself in work, the more my personal life suffered. The thing that made it more tolerable was drinking.”

His drinking escalated over the years. At its worst, his drinking occurred during every one of his days off — about 30 beers and six to seven shots per day.

“If I wasn’t drinking, I was at work having withdrawals. Anxiety, shaking hands — I had it all,” he says.

The fire fighters under Talbott’s command noticed, too.

“There would be days at work where people would notice the shaking or that my face was flushed,” he recalls. “They’d say, ‘Man, are you okay?’”

Talbott thought he was hiding his struggles, but his colleagues saw right through it. The hopelessness and despair he felt was so acute that he attempted suicide twice.

“Both times, I was cleared to go back to work, which was surprising to me,” admits Talbott.

Fire fighters face startling odds when it comes to suicide – almost 20 percent of more than 1,000 fire fighters surveyed have reported making plans to commit suicide, according to a 2015 study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Talbott the day before he stopped drinking, after falling on a coffee table while drunk and needing 20 stitches.

Talbott’s rock bottom didn’t come until after he retired. That was when he knew he had to get help.

“Up until then, I was in complete denial,” he says. “I just thought I wasn’t managing my life appropriately. I completely ignored the post-traumatic stress disorder part of it and just thought I was a drunk.”

He entered rehab and started working with a counselor. He learned how to put his feelings in order and manage his thoughts in a positive way. Counseling taught him management techniques to fall back on.

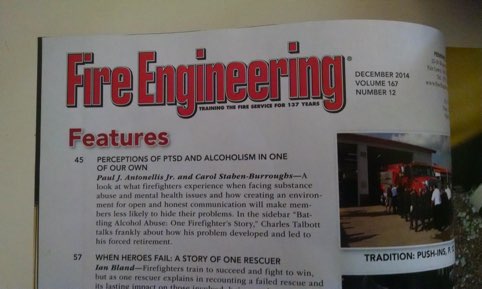

In 2014, Talbott was asked to write about his struggles with PTSD and substance abuse for Fire Engineering magazine.

“The bottle wasn’t going to fix it or make it go away,” he says.

Talbott still struggles with flashbacks, anxiety and hypervigilance, but he knows how to cope with those symptoms in a healthy way.

“Things are a million times better now,” he says. “I’ve been sober for more than two years. I never thought that would happen. I am accountable to myself.”

As part of his recovery, an article Talbott wrote in Fire Engineering magazine, “Battling Alcohol Abuse: One Firefighter’s Story,” opened conversations about post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol abuse within the fire service. Talbott feels like it was his contribution to help other fire fighters suffering from the same behavioral health issues.

Currently, Talbott works as a mentor, facilitator and community advocate with a 12-step program, helping other members stay sober.

“I became a fire fighter to help people,” Talbott says. “The fact that I had to retire out of it because of post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol is devastating. If a rehab center just for fire fighters had existed earlier, my story might have ended differently.”